If you were tasked with answering it, what would your first step be? Would you scribble down your thoughts — or would you Google it?

Terry Heick, a former English teacher in Kentucky, had a surprising revelation when his eighth- and ninth-grade students quickly turned to Google.

“What they would do is they would start Googling the question, ‘How does a novel represent humanity?’ ” Heick says. “That was a real eye-opener to me.”

For those of us who grew up with search engines, especially Google, at our fingertips — looking at all of you millennials and post-millennials — this might seem intuitive. We grew up having our questions instantly answered as long as we had access to the Internet.

Now, with the advent of personal assistants like Siri and Google Now that aim to serve up information before you even know you need it, you don’t even need to type the questions. Just say the words and you’ll have your answer.

But with so much information easily available, does it make us smarter? Compared to the generations before who had to adapt to the Internet, how are those who grew up using the Internet — the so-called “Google generation” — different?

Heick had intended for his students to take a moment to think, figure out what type of information they needed, how to evaluate the data and how to reconcile conflicting viewpoints. He did not intend for them to immediately Google the question, word by word — eliminating the process of critical thinking.

More Space To Think Or Less Time To Think?

There is a relative lack of research available examining the effect of search engines on our brains even as the technology is rapidly dominating our lives. Of the studies available, the answers are sometimes unclear.

Some argue that with easy access to information, we have more space in our brain to engage in creative activities, as humans have in the past.

Whenever new technology emerges — including newspapers and television — discussions about how it will threaten our brainpower always crops up, Harvard psychology professor Steven Pinker wrote in a 2010 op-ed in The New York Times. Instead of making us stupid, he wrote, the Internet and technology “are the only things that will keep us smart.”

Daphne Bavelier, a professor at the University of Geneva, wrote in 2011 that we may have lost the ability for oral memorization valued by the Greeks when writing was invented, but we gained additional skills of reading and text analysis.

Writer Nicholas Carr contends that the Internet will take away our ability for contemplation due to the plasticity of our brains. He wrote about the subject in a 2008 article for The Atlantic titled “Is Google Making Us Stupid.”

“… what the [Internet] seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation,” Carr wrote.

The few studies available, however, do not seem to bode well for the Google generation.

A 2008 study commissioned by the British Library found that young people go through information online very quickly without evaluating it for accuracy.

A 2011 study in the journal Science showed that when people know they have future access to information, they tend to have a better memory of how and where to find the information — instead of recalling the information itself.

That phenomenon is similar to not remembering your friend’s birthday because you know you can find it on Facebook. When we know that we can access this information whenever we want, we are not motivated to remember it.

‘I’m Always On My Computer’

Michele Nelson, an art teacher at Estes Hills Elementary School in Chapel Hill, N.C., seems to share Carr’s concerns. Nelson, who has been teaching for more than nine years, says it was obvious with her middle school students and even her 15-year-old daughter that they are unable to read long texts anymore.

“They just had a really hard time comprehending if they went to a website that had a lot of information,” Nelson says. “They couldn’t grasp it, they couldn’t figure out what the important thing was.”

Nelson says she struggles with the same problem.

“I’m always on my computer. … I don’t read books as much as I used to,” she says. “It’s a lot harder for my brain to get to a place where I can follow and enjoy the reading, and I get distracted very easily.”

The bright side lies in a 2009 study conducted by Gary Small, the director of University of California Los Angeles’ Longevity Center, that explored brain activity when older adults used search engines. He found that among older people who have experience using the Internet, their brains are two times more active than those who don’t when conducting Internet searches.

Internet searching, Small says, is like a brain exercise that can be good for our mental health.

“If somebody has normal memory when they’re older, I always encourage them to use the computer,” he says. “It enhances our lives.”

For Small, the problem for younger people is the overuse of the technology that leads to distraction. Otherwise, he is excited for the new innovations in technology.

“We tend to be economical in terms of how we use our brain, so if you know you don’t have to memorize the directions to a certain place because you have a GPS in your car, you’re not going to bother with that,” Small says. “You’re going to use your mind to remember other kinds of information.”

How To Teach Digital Natives?

Heick has since left teaching to start TeachThought, a company that produces content to support teachers in “innovation in teaching and learning for a 21st century audience.”

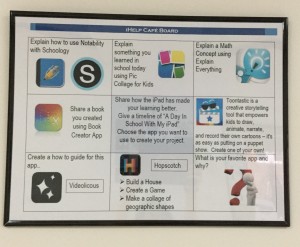

To him, the Internet holds great potential for education — but curriculum must change accordingly. Since content is so readily available, teachers should not merely dole out information and instead focus on cultivating critical thinking, he says.

“Classroom walls and school building walls are transparent, with technology essentially bringing the outside world to the classroom and vice versa,” he says.

Heick says his company recently started working with schools and organizations in a few states, including North Carolina, Texas and New York, to develop lesson plans.

“Google really lubricates that access to information and while that is fantastic, it makes us have to change a bit the way we think about things,” Heick says. “Because we’re so busy, we have this false security that we understand something because we Googled it. Now we’re moving on to the next thing instead of really rolling around with this idea and trying to understand it.”

One of his recommendations is to make questions “Google-proof.”

“Design it so that Google is crucial to creating a response rather than finding one,” he writes in his company’s blog. “If students can Google answers — stumble on (what) you want them to remember in a few clicks — there’s a problem with the instructional design.”

Meanwhile, teenagers are also aware of how the Internet is taking ahold of their lives. Caitlyn Nelson, teacher Michele Nelson’s daughter, finds it hard to focus when she is forced to do readings or even exams online. Like most teenagers, sometimes she finds herself surfing the Web when she’s supposed to be reading PowerPoint slides in class.

Caitlyn talks about a video they watched in English class about the impact of technology.

“We talked about how technology is changing … how most people are basically becoming zombies and slaves to the Internet because that’s all we can do,” she says.

“I feel really bad that I’m connected to my phone all the time instead of talking to my mom. But she’s also addicted to her phone.”

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))