How did this happen?

Little teaches at Martin Luther King Jr Middle School in Berkeley, California, where classes like sewing, woodshop, and metal shop — what she calls “practical ways of learning math” — are no longer offered; tight budgets and renewed emphasis on academic learning have eliminated them. But Little couldn’t bear to subject already disengaged students to yet another ho-hum class of multiplication tables and long division.

Instead, she took a gamble and brought some materials to school for her students to play with: a sewing kit, the 3-D doodler she’d just been given, her son’s marble-run set and a MaKey MaKey device she knew nothing about, donated by a friend.

To Little’s surprise, the students dove in. They put themselves in their own groups based on personal interest, and worked together to grapple with these mysterious tools. Little herself was unaware of the MaKey MaKey instrument. “I’m afraid of maker-type technology,” she told me. But she imagined that she and the students could figure out together how to use the alien circuit board to interesting effect.

“I didn’t know how to do it, but I could teach them how to learn,” she said.

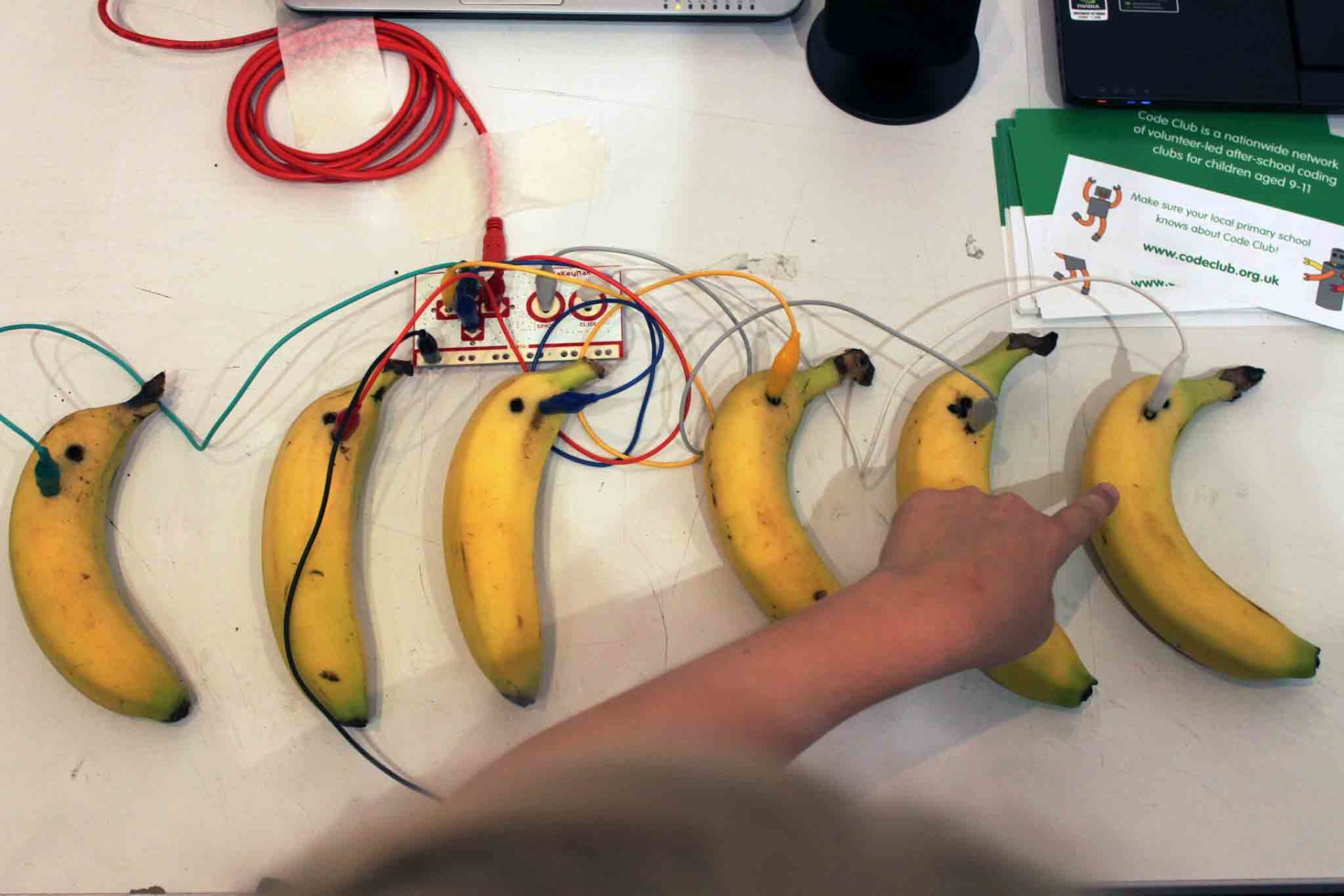

Inspired by an online investigation, one group of students decided to build a banana piano. This meant they needed to program the computer — Little’s laptop — to the MaKey MaKey circuit board, which the students were able to do. Then, by trial and error, the 12-year-olds learned how to build a full circuit: They attached one set of wires from the circuit board to six bananas (borrowed from lunch), and another connector to the laptop.

Little gets fuzzy explaining exactly how the banana piano worked. “I could not build one,” she said. But the students understood, and one day they brought the unorthodox instrument to the entire regular math class.

“They played a song for everyone, and everyone went wild,” Little said. “’We want to come to math support!’” she recalled the students saying.

Little then invited all her math students to attend the twice-weekly optional remediation classes where she’d first introduced the practical tools. “They all opted for extra math,” Little said.

Intrigued by the bananas, one group worked with lemons, this time completing the circuit by holding hands. The electricity ran through every kid in the class to the last one, who could then “play” the lemon bongos. Kids with a more literary bent wrote a book and set music to it; they rigged the MaKey MaKey device to play exciting music during adventurous passages and dirge music during sad ones. Other students flocked to the sewing, 3-D pen and marble maker, including one child who cross-stitched the emblem of the San Francisco Giants as a gift for his grandmother.

Student Empowerment

The learning didn’t stop when supplies finally dwindled. Rather than solicit parents for money, Little turned the need for materials into an immersion in marketing and sales. They would sell pencils, the children decided, but at what price? They debated strategies: If we sell 60 pencils at $2 per pencil we’ll reach our goal. But who will spend that much on a pencil? Maybe 50 cents per pencil this week, and 75 cents every day thereafter.

“The kids were totally in control of how the price would vary and how it would affect profit,” Little said. In the end, the children earned $120, enough to resupply the 3-D doodler, buy more circuits and restock the sewing basket.

Little is astonished by the changes she saw among her students. By making the classroom hands-on, she upended the traditional social hierarchies: Kids who might have been ostracized for being deficient in math were suddenly valuable when their strengths — like problem-solving or brainstorming — became visible and needed.

Likewise, the stigma attached to remediation classes, and even to math itself, disappeared. Everyone wanted to join in. In addition, kids abandoned their usual roles: Some who traditionally sat quietly and waited for direction began to take charge, and others who claimed to hate reading devoured turgid manuals. And Little herself became more of a facilitator than an instructor, helping kids find what they needed but not spoon-feeding them information.

“Teachers are no longer the holders of all knowledge,” she said. Rather, the students themselves, having discovered on their own how to program fruit to play a tune, developed unexpected confidence.

“They became bold and self-directed when they realized I did not have the answers,” Little wrote about the experience. “I became a curious and excited partner in their discoveries.” She shared her findings at the FabLearn conference at Stanford and wrote a report about the results.

When school began in September, Little brought back the MaKey MaKey contraption and other tools to her classroom, this time introducing them to all her students from the start. She remains ebullient about the possibilities, and encourages her math-teaching peers to give it a try.

At a minimum, teaching this way satisfies the Common Core requirements for students to solve problems and understand concepts, she said.

“Math teachers who have only paper and pencil at their disposal, find some of these important standards very difficult to illuminate,” according to Little. “When students must work in groups to complete a real project, all of these mathematical standards come into play. Instead of being told, ‘Your calculations are wrong,’ students experience a real setback in their creation and must problem solve to get it working.”

She discovered that this approach stimulates children to learn, helping them to understand and use math in ways they’ve never considered. For example, Little uses cross-stitch to develop understanding of math.

“Cross-stitch is like creating art with pixels,” according to Little. “You cannot actually make a curve but can approximate one by using a stair step method. Distance from the piece creates the illusion of a smooth curve.” She said students were excited by this discovery and were giving feedback on one another’s projects.

Little had hesitation over these new maker tools, but she saw in them the same qualities that made sewing and wood shop classes a practical way of learning math, back when they were available. Both require planning, visualization and precise measurements. Educators may not feel fully prepared to start these hands-on projects, but Little says not to worry about lesson plans or about not fully understanding how it all works. “Just start,” she said. “Get some supplies and go. Don’t be afraid!”

Adam Coulter Johnson currently teaches 8th grade Pre-Algebra in Mountain Brook, Alabama. This fall marked his tenth year as an educator. He has flipped his classes for the last four years and continues to learn about its benefits with each lesson.

Adam Coulter Johnson currently teaches 8th grade Pre-Algebra in Mountain Brook, Alabama. This fall marked his tenth year as an educator. He has flipped his classes for the last four years and continues to learn about its benefits with each lesson.